Juggling the demands of home and work has never been more complicated. Grown children often live far from their aging parents. Even if they are close by, they are frequently midcareer themselves, with many work responsibilities. Plus, 30 percent of family caregivers have children or grandchildren living at home while they are also caring for an aging relative.

If any of this sounds familiar, you are not alone. According to a report by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving, one in six households is caring for an older adult. The good news is that there is a variety of programs that can help pull together the assistance you need.

One of the biggest issues in getting help is overcoming your own feeling that you are supposed to do it all. (Or your parent’s pressure that it needs to be you.) Part of working with your family member as a team includes being honest with yourself and honest with your relative about what you can and can’t do. Then you can solve problems together to find workable solutions that meet everyone’s needs.

You can make your life easier, and find the help you need more efficiently, if you consult with an Aging Life Care™ Manager. These professionals know the local programs and eligibility requirements, which can help save you time and energy.

An Aging Life Care Manager can

- make a home visit to discuss concerns with your parent

- conduct a complete assessment of needs

- make recommendations tailored to your parent’s preferences, resources, and support system

- hold a family meeting to build consensus

Below are some tips for creating support systems that can help your loved one stay at home for as long as is safely possible:

Identifying the help you need

Those who have cared for a loved one for a long time know they are able to do a better job when they accept help from others. Even when you enjoy the process, it can still be a lot of work. And caring for an aging parent may go on for an extended period of time. You need to pace yourself, and willingness to accept help is the first step.

For many family caregivers, noble but skewed beliefs can keep them from reaching out for help:

- “I should be able to do this by myself.”

- “It’s selfish to think of my own needs.”

- “My [brother/sister/cousin …] won’t do it the right way.”

- “Dad won’t let anyone help but me.”

If these thoughts sound familiar, you are not alone. Beliefs such as these, however, represent an unfairly distorted view. They don’t take into account the realities of modern life. And they can interfere with your ability to care for your parent for the long term.

When left unchecked, such beliefs may lead to depression and burnout. In fact, family caregivers have a much higher incidence of depression and greater health problems than do their noncaregiving peers.

You can learn to pace yourself and accept help by combating these distorted beliefs. Professionals in cognitive therapy say the simplest way is to recognize your negative self-talk and offer yourself an alternate view. For instance:

“Should” statements. Idealistic thoughts focused on how things “should” be rather than on adapting to the realities of a situation.

- Alternate perspective.Instead of “I should do it all,” remind yourself, “I would prefer to do it all, but that’s not possible. It’s better that I get help than exhaust myself and do a bad job with Mom.”

Labeling. Applying false or harsh judgments to yourself or others.

- Alternate perspective.Instead of “It’s selfish to think of myself,” remind yourself, “I do a lot to care for Pop. But I also need to pace myself for his sake as much as mine. That’s not selfish.”

The types of help families often seek. Once you realize you can’t do it all, think through which tasks you feel most comfortable having others do. One approach is to list everything you do, divided into the following categories:

- Tasks you enjoy (keep these). Taking Mom clothes shopping or working in Dad’s garden.

- Tasks others can do for free (varying reliability). Running errands. Periodic light housekeeping (laundry). A meal now and then.

- Tasks that can be hired out (very reliable). Housekeeping. Yard and home maintenance. Shopping and errands. Meal preparation. Transportation. Personal care (bathing, dressing, toileting).

- Tasks that require special skill or attention. Filling pillboxes and managing prescription refills. Going to the doctor. Coordinating treatments and care services. Paying bills and balancing the checkbook. Monitoring assets.

- Tasks that provide emotional support. Checking in about issues. Trips for socializing and recreation. Visiting when in the hospital.

Which of these tasks do you want to keep? Depending on your relationship and how close by you live, you might choose the first and last (those you enjoy, and those that provide emotional support). Tasks that need special skill or attention might be something you would prefer to do, but they can be hired out. You’ll want to find skilled professionals to handle them. (A daily money manager for bills. An Aging Life Care Manager for doctor visits and coordinating treatments and care.) An Aging Life Care Manager can also help you review your list and find local providers that will fit with your needs and budget.

What inaccurate beliefs are you holding onto that keep you from getting help? How might you change your self-talk about them? Provide an alternate perspective?

Return to top

Tips for letting others pitch in

Caring for an aging parent has many rewards. Still, you need a break now and then to recharge your batteries. Many family caregivers don’t take needed breaks because they worry that others won’t do a good-enough job in their place.

Although concern for your parent’s comfort and safety is appropriate, it’s also important to distinguish between real threats and a tendency toward perfectionism. For instance, it’s not uncommon for one sibling to feel like none of the others help. At the same time, the other siblings feel there “isn’t enough room” for them to pitch in, because the primary caregiver is so particular about if, when, and how things get done.

And while perfectionism may appear to be important in achieving quality care, it frequently backfires. Perfectionists tend to look at the results and forget that the process is equally important in eldercare. (For instance, your parent is more than a “to-do” list. They also want to have an emotional connection with you.) Perfectionists also tend toward depression and anxiety because the pressure to constantly live up to their own expectations can be overwhelming. In addition, perfectionism is overwhelming for siblings or employees who want to help. They wind up feeling that it’s impossible to do a good job, so they stop trying, leaving you alone with all the care.

Voltaire once said, “The perfect is the enemy of the good.” If you are having trouble getting, or allowing, others to help, consider the following:

- Is a hot dinner every night necessary, or could Dad be just as satisfied by a hearty sandwich?

- Your sister might not do your mom’s hair just right, but the tradeoff may be an opportunity for them to rekindle their relationship.

- As a compassionate friend, what advice would you give someone in a situation similar to yours?

If the perfect is getting in the way of the good for you, it can be hard to let go. The stakes seem very high. Be gentle with yourself, and look at these tips from researchers in the field of perfectionism:

- Start small.Ask someone to take over a routine task, such as picking up a prescription.

- Consider it an “experiment,”not a permanent change.

- See what happens.If things don’t go as planned, were the errors life threatening for your loved one or simply irritating for you?

- Were there any positives to the situation?Did they have value?

- Try again.Don’t expect it to be easy the first time. As with any learning process, the more you do it, the more comfortable it will feel.

How does the perfect get in the way of the good in your caregiving life? Start small. As an experiment, what little task are you willing to ask for help with?

Return to top

When your loved one refuses outside help

Okay. You’ve decided it’s time for some caregiving help for your parents. The next obstacle may be that Mom or Dad doesn’t want anyone to help. Or if they do, they want “only you.”

Part of working together as a team is learning more about your parent’s priorities. Their concerns are important. By listening, you will likely come to understand the reasons for their refusal. Even if they have dementia, you will learn more about what’s at the emotional root of it—perhaps confusion, anger, or distress about the changes of aging. As you talk openly, you may discover that your loved one is depressed or worried about something they haven’t shared with you before. With genuine curiosity and compassion, ask them to tell you why they don’t want help from others, and truly listen to their issues.

Concerns may include the following:

- Theft. Worry about robbery is common.

- Privacy or shyness. It’s awkward to have strangers in the house.

- Cost. A very real concern.

- Dignity. It may be difficult for your loved one to admit they need help.

- Loss of independence. It feels like others are taking over their life.

- Fear of death. Acceptance may feel like the beginning of the end symbolically.

Begin by validating their issues. Resist the urge to present solutions right away. That creates an argumentative feeling. Repeat what you understand of their issues. Ask to learn more. This shows your respect for what is important to them and lays a foundation for teamwork. Your relative may not be comfortable with the concept of collaboration: They are the parent, you are the child. That will always be the case. (You will never be the parent.) But your family roles are also changing, and that can be difficult. It will take some time for everyone to adjust to new responsibilities and shared decision making.

If your relative has cognitive impairments—memory or thinking problems—teamwork may not even be possible. But starting with a show of respect speaks to the heart and comes through, even with people who have dementia.

As a side note: Atul Gawande, author of “Being Mortal,” notes that children are most worried about their parent’s safety. Meanwhile, the older adults themselves care less about safety, placing their highest priority on autonomy and independence. Understanding your loved one’s motivations will help you find solutions more easily.

Share about your own needs. This requires some vulnerability on your part. And some consideration of what those needs are. You don’t have to compare who has the greater need, you or your loved one. This conversation is simply about getting all the issues out, with your needs every bit as important as theirs.

Needs to consider:

- Time for work or other family responsibilities

- Tending to your own health (or employment or marriage, if that’s true and is reasonable to share)

- A desire to preserve the emotional connection with your loved one (by not having all your time taken up with chores).

Ask your loved one to accept help “for you.” This may or may not resonate. But when presented this way, some parents can be willing to try something outside their comfort zone.

As appropriate, offer reassurance that you are not abandoning them, that you will be there for the big or important tasks (medical visits, emotional support, managing finances). Let them know that you just need help with the things others can do (housekeeping, errands) or where a professional might be more appropriate (working with doctors, for instance, or bathing, if that type of intimacy between you is awkward).

Then brainstorm about solutions:

- Is there a friend, neighbor, or member of their faith community who could help?

- Home care agencies and registries do background checks. They also have processes that provide protections concerning personal property.

- Check with EldercareLocator.gov for low-cost options or programs. (It may be a while before they can call you back. They often have a backlog of cases.) Or consult privately with an Aging Life Care Manager. They can save you time and energy because they know the local providers and local programs. They can help you find benefits your loved one may qualify for and get the best match for your situation.

- This may take several conversations. It’s a big change. They need time to get used to the idea and make it their own. Keep it a discussion. Ordering them around or nagging may backfire.

- Suggest looking for housekeeping help first. That’s often an easy way to introduce the idea of someone coming into the home. Also emphasize that it’s just temporary, to see what it’s like. If your relative doesn’t feel boxed in, they will be more willing to give it a try.

- Include your loved one in the selection of the agency or helper. This gives them a sense of control and buy-in.

- Start slow. You don’t need to go all in with everything at once. Perhaps you can even be there the first few visits to help with orientation and smooth the interactions as you offer tips for doing the laundry or show where the vacuum is kept.

You may need to set limits. If your loved one cannot see the team context, then you may have to frame the situation in a more structured and assertive way. State specifically what you are able to do, and offer suggestions for the things you cannot do. Start small and whenever possible, involve your family member in choosing who will help and when they will come. For example:

- “I can help on the weekends. But that still leaves Wednesday, which I can’t do. Of the two agencies we interviewed, which one did you like best?”

- “I know you feel most comfortable with me, but [other relative] wants to participate, too. Let’s have him come one day next week, just to try it out. What day would work best for you?”

Unless it truly would put them in danger, you may need to stop helping as much. Their autonomy and your relationship may be more important than their getting all the help you think they need. They are grown-ups, after all. And so are you. You need to take care of yourself.

An Aging Life Care Manager can assist you in the process of setting limits wisely. They can even facilitate a family meeting, contributing their experience with elders and their knowledge of local resources.

Why do you think your loved one is refusing help? How might you address their concerns and still express your need for assistance?

Return to top

A tool for organizing friends and family

Some tasks are more than one would ask a friend or unskilled helper to do. But bringing a meal or taking your parent shopping is simple. And even having one less thing on your To Do list can be a big relief.

Family caregivers often report the most difficult part is the act of asking someone to help. That’s understandable. We’re all busy. You don’t want to intrude. Friends and relations even say, “Keep me posted, and let me know if there’s anything I can do.” But it’s hard to remember and follow up when the time comes and you realize you could use a helping hand.

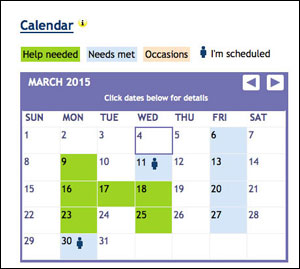

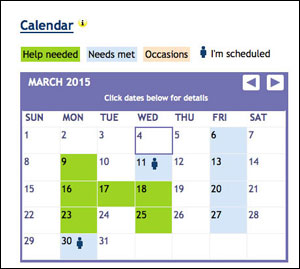

With the Internet, tools are now available that can help everyone stay more connected. One especially useful tool is a simple, free, online calendar service offered by Lotsa Helping Hands, a nonprofit technology company.

Lotsa Helping Hands allows you to create a “community” of interested individuals. You enter their names and email addresses into your account and can easily send updates about your loved one’s condition. (For those familiar with the Internet, this online service is like a private, family blog.) You can upload photos. People can write back. Conversations can occur online. Only people you have authorized to be part of your online community will have the login information needed to participate.

Lotsa Helping Hands allows you to create a “community” of interested individuals. You enter their names and email addresses into your account and can easily send updates about your loved one’s condition. (For those familiar with the Internet, this online service is like a private, family blog.) You can upload photos. People can write back. Conversations can occur online. Only people you have authorized to be part of your online community will have the login information needed to participate.

The calendar tool is what makes Lotsa Helping Hands special. No longer do you have to make embarrassing phone calls asking for help. No more leaving messages and getting three positive responses. Then you have to call two people back and say no, but ask them to please respond next time…

With Lotsa Helping Hands:

- You post an errand on the calendar (e.g., take Mom to hairdresser, Weds. 3:00).

- You send an email request to people in your community.

- A community member willing to help clicks on the task on the calendar.

- Anyone coming after that sees the task is taken.

- You and the helper receive an email confirmation.

- Email reminders are sent to you and the helper a week before and the day before the task.

Now when someone asks, “Is there anything I can do to help?” you can reply, “Yes, give me your email address. I’ll keep you updated on Mom. And if we need something, I’ll send you an email.”

No fuss, no muss. And to top it off, there is no charge to open an account at Lotsa Helping Hands. It’s free!

Return to top

Services to help at home

Services received in the home are divided into three types. Which service you choose depends on the level of staff training needed. Requirements set by Medicare may also determine which type of service will be covered.

- Home health care. This service is provided by nurses and other medical professionals.

- Home care. This service is provided by nonmedical staff.

- Hospice care. This service is specifically for persons with a life-limiting condition. Services are provided by nurses and other medical professionals.

Home health care is short-term medical care given to help an individual regain their health. Typically, home health care is used following a hospitalization or surgery. The role of the staff is to assist homebound patients with a complicated medical condition that can be managed or improved with the help of a medically trained specialist. It might be a registered nurse, a physical therapist, a speech pathologist, or an occupational therapist.

Home health care normally involves hour-long visits once or twice a week over a span of one or two months.

Home health care is covered by Medicare or other health insurance, but there may be requirements for eligibility, such as the inability to leave the home easily and a recent surgery or hospital discharge. A doctor’s order is required.

If your family member needs 24/7 access to medically trained staff, home health will not cover it. It’s very expensive to hire a registered nurse 24/7 for home care. A skilled nursing facility is the most affordable option. Medicare and most insurance will pay for a skilled nursing facility for a limited time. A doctor must determine that your family member needs round-the-clock access to medical attention.

Home care is nonmedical care to help a person remain in their own home. There is no need for a doctor’s order. Nonmedical home care includes

- personal care (such as bathing, grooming, and toileting)

- dressing and undressing

- fixing meals

- assisting with walking

- transferring in and out of a chair or bed

- light housework

- transportation

- visiting and companionship

Nonmedical care does not mean the caregiver lacks skills. The individual caring for your family member needs to understand the basics of eldercare. Although certification is not necessary, many in-home care providers are certified nursing assistants or home health aides. They may have gained their initial training and experience in a nursing home. Now they prefer to work one on one with clients in the home.

Nonmedical care at home can be vital to keeping your parent independent and safe. Unfortunately, health insurance, including Medicare, does not typically cover nonmedical care. If your family member has long-term care insurance or veterans benefits, nonmedical home care may be covered. And there are a few Medicare Advantage plans that might offer it. Check your family member’s policies or contact the Veterans Administration for details.

Some nonmedical home care may be available for persons with low income. If your parent is on Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income (SSI), contact the local Area Agency on Aging. The state Medicaid office or local Veterans Service Office may also be able to help. Hiring an Aging Life Care Manager, who knows community resources, may be the most efficient way to find low-income services. An Aging Life Care Manager can determine whether your relative is eligible for local programs. In addition, they know whether a waiting list is in place and how best to apply.

Hospice care is medical care for individuals with life-limiting illnesses. Like home health care, hospice involves weekly hour-long visits from medical professionals. Both the patient and the family have access to a variety of support services. A doctor must recommend hospice based on a diagnosis of an incurable condition. In addition, the doctor must estimate that the patient has six months or less to live.

Hospice care emphasizes quality of life using a team approach. The focus is on keeping the patient comfortable emotionally, physically, and even spiritually.

- Nurses and physicians help manage difficult symptoms (pain, nausea, fatigue).

- Social workers and chaplains assist with emotional and spiritual issues (anxiety, depression, spiritual distress).

- Nurse aides come several times a week to bathe and groom the patient.

- A volunteer is available to give family members a few hours off each week.

Hospice does not hasten death. In fact, there are studies that demonstrate hospice care often results in people living longer—as well as more comfortably—than they would have lived without it.

Most people wish they had received the support of hospice earlier in their condition. Patients on hospice understand that their condition does not have a cure. They are willing to forego curative care. Instead, they wish to focus on improving the quality of the time that remains to them. Hospice is available for six months, but can be extended if the patient lives longer.

Hospice is for more than just cancer. Most people think of hospice in terms of a cancer diagnosis. In fact, hospice can provide powerful support for individuals with other incurable conditions, such as COPD, heart failure, and advanced dementia.

Hospice care is 100 percent covered by Medicare. If you think your loved one has a life-limiting disease, ask the doctor if hospice is appropriate. If so, you have a choice of hospice providers in your community.

Which of these services seems the most appropriate for your situation? Home health (medical)? Home care (nonmedical)? Hospice?

Return to top

Hiring help yourself

Hiring someone directly brings many risks and many responsibilities. If you want to go this route, make sure you are well informed. Simple as the caregiving job may seem, being an employer is not easy. And bringing strangers into the home is not a small matter. You may want to go through a home care agency because they handle the administrative end. However, you don’t generally get to pick your caregiver. You do get to pick with a registry or direct-hire company. They will assist with some of the screening, but the responsibility for hiring and firing, supervision, payroll and taxes, etc., lands on you as the employer. Some registries include a payroll service to help you with that. Or you can locate a payroll service on your own.

Here are some things to keep in mind if you hire someone yourself:

- Criminal background checks. You want to be sure that the person coming to your loved one’s home does not have a history of elder abuse or run-ins with the law. Even the nicest seeming people can be trouble. Con artists typically have winning personalities.

- Immigration status. Many home care workers are immigrants. It will be your responsibility to verify their ability to work legally in the United States. Make copies of passports or green cards for everyone you hire, and record their tax ID number.

- Driving record. If the home care provider will be driving your loved one, get a copy of their driver’s license and check the Department of Motor Vehicles for accident and ticket history. You might also ask for a copy of their auto insurance card if they will be using their own car.

- Drug screening. You want to be sure that the person caring for your loved one is mentally sound. You don’t want someone in the house who is working while under the influence of drugs. If you decide you want to require drug testing, be prepared to pay for the expense.

- Home security. From protecting Mom’s valuables to arranging for a key, there’s a delicate balance between convenience and caution. (Experienced home care professionals have systems to make sure your family member’s home is appropriately protected. They know how to minimize hassles for your parent and the caregiver while providing security for your loved one’s assets. They are usually required to also have insurance against a possible theft.)

- Training and expertise. How do you decide if the caregiver really knows and understands eldercare? Can they handle an emergency and make good decisions? Do you have the time to verify training and educational certificates? Just because a person says they have done something before, doesn’t necessarily mean they have. You’ll also want to check with your loved one’s long-term care insurance to verify that they will pay for this individual’s services. Sadly, competence is hard to verify unless you are experienced with recruitment and hiring. (Home care professionals test for competency. And many provide training opportunities for their employees.)

- Reliability. Get at least two or three references and call them. Verify dates of employment and ask about their skills, compassion, timeliness, etc. A key question is, “Would you hire them again if you had the need?”

- An honest accounting of hours. Unless you are present much of the time, how will you know that the caregiver worked the hours they bill you for? If your loved one is unwell or has memory problems, they may not be able to monitor time spent providing care. (Home care professionals have systems in place to confirm the hours worked.)

- Expectations. In addition to hourly rate, tasks to perform, and when and how they will get paid (for example, by check once a week), you will need to clarify other expectations. Can they smoke in the house? (Are they okay providing care if your loved one smokes in the house?) Do they bring their own food, or can they eat from the meals they prepare for your relative? What is your policy about personal phone calls while on the job? Is there a pet they need to also take care of? (Do they even like cats? Any allergies?). What should they keep track of during their shift (medications taken, food eaten, sleep schedule, activities …). What happens when family comes to visit or your loved one is in the hospital and you don’t need their home care services? Do they get paid anyway? How much notice can they expect?

- Quick replacements if the caregiver is sick. By hiring the caregiver directly, you are the employer. That means you need to be ready with your own Plan B in case the caregiver is unable to come to work. Is your parent safe without assistance for a day? Two days? Three? Or are they dependent on the caregiver for meals? Medication reminders? Supervision to make sure the stove is turned off or to prevent wandering? Once you become the employer, you have to not only hire the employee, but also be ready with an alternate plan if your employee gets sick. (Some registries can help you with a substitute. Ask if this is a service they offer.)

- Protection from lawsuits if the caregiver gets hurt. If you hire someone on your own, they may file a lawsuit against you if there is an injury on the job. As the employer, you are required to pay workers’ compensation Insurance to cover potentially disabling incidents. (Call your homeowner’s insurance and see if your liability coverage applies.) Without coverage, your assets are at risk because you are individually liable. A home care agency provides this coverage because they are the employer.

- Social Security and other taxes.As an employer, you are responsible for Social Security, payroll taxes, and unemployment insurance. There are many legal obligations, deadlines, and penalties if you do not comply. To hire someone legally as a contractor rather than as an employee, their terms of engagement must fit the criteria of the state’s labor code. A person may say they are an independent contractor, but that claim can be called into question if you set the days, hours, and duties. (The IRS says this makes them employees.) If they do not qualify as an independent contractor and they are being paid without taxes being withheld, it is against the law. If it is found that you or your parent were the employer, you must pay all back payroll taxes plus penalties. You might even have to appear in court. If you plan to hire help directly, check with an accountant or hire a payroll service to find out what your tax responsibilities are.

- Discipline, hiring, and firing. If only all employee/employer relations were trouble free. Unfortunately, they are not. You should have a job description prepared before interviewing. Once someone is hired, there will be a period of getting used to each other. Your loved one will have preferences, and so will you. Your employee will need some training concerning household patterns. Communicating these priorities effectively is an art. Enforcing them is even more delicate. Then there is the matter of compatibility. Not all personalities are a good fit. If differences are irreconcilable, letting an employee go is yet another art, though one that may have legal and financial ramifications. Make sure you understand the state and federal laws about this subject. Moreover, if/when you do let someone go, depending on your loved one’s needs, you may have to have someone else chosen, screened, and ready to put into place, perhaps even the next day.

Unless you work with a home care professional, you will want to work with an attorney to prepare a contract that covers the necessary clauses so you don’t find yourself in a situation where you are exposed to legal liability.

As you can see, hiring help directly is certainly an option, but it is not as simple as it may seem. This is why many families turn to an Aging Life Care™ Manager to get a referral for the best blend of support and do-it-yourself options. An Aging Life Care Manager knows the different local providers, including home care agencies, registries, and payroll services. They can explain the legalities and help you be sure you find a good match.

How will you address issues such as payroll taxes, workers’ compensation, and background checks? What about when the caregiver is sick and cannot come in?

Return to top

Lotsa Helping Hands

Lotsa Helping Hands